This is my recipe for sourdough. A lot of credit goes to Michael O’Malley, who gave me his starter and got me going, and a lot of credit goes to a multitude of books I’ve read. These folks are responsible for anything I say that’s helpful; I’m responsible for all of the things that are wrong or unhelpful.

One principle I particularly want to call out is: always bake two loaves. It’s part of O’Malley’s art practice to give loaves to people, and it’s certainly the genial thing to do. I’ve made it my practice, too… and I always make sure to give away the better loaf. You’ll get better at baking quickly, and you’ll make new friends to boot.

A dose of perspective

I didn’t think this would be a four thousand word document when I started writing. Baking is a journey. I’ve tried to write down all of my process to make that journey easier for you, but I’m sure it’s overwhelming.

If you don’t have a bread you bake regularly using commercial yeast, I think it’s best for your sanity to get a few loaves under your belt before you try sourdough. Try a no-knead bread recipe and bake it three or four times to get a little bit of a confidence. Once you’re feeling good and have a sourdough mother, read the “making your starter” section below. Expect things to rise more slowly with the sourdough than they did with the commercial yeast. Be patient, and it will be delicious.

Terminology

- Flour is wheat flour. Only white all purpose (AP) or white bread flour should go in the mother; you can use just about anything you want in the starter and dough.

- Water is room temperature, clean, filtered water. We have an inline filter in our sink in Claremont and that definitely improves the flavor of bread (and anything else we cook with or in water).

- Salt is kosher or sea salt, not iodized salt. Iodine doesn’t get along well with most bacteria—including the lactobacillus that’ll put the sour in your sourdough.

- The mother is the sourdough you keep. This is the mother lode, the supply on which you must not get high. I keep mine in the fridge.

- Starter is made from the mother. It’s what you use to, uh, start a loaf of bread. It’s made up fresh each time you bake.

Making the mother

I’ve never made my own sourdough mother, so I can’t tell you much about it. Seamus Blackley has plenty of good advice on the subject. Or I can dry some out and mail you some. But once you have it, these instructions are for you.

Keeping the mother

My sourdough mother lives in the fridge, weighing in around 250g. To stay healthy it should be fed minimum once a month. I feed every time I bake, typically baking once a week—plenty for keeping the starter healthy. If you need to feed your starter but don’t have time to bake, follow the steps below at “Making your starter”: pull out 100g or so of mother, and add back in to the mother 50g water, mix, and then add in 50g flour. If you’re not using the 100g of mother to make a starter, discard it in the compost or trash.

I like to have about twice as much mother as I’ll be taking out to make starters. Since I’m typically baking two loaves that want 100g starter each, that means I need 200g starter each time I bake. Half of the starter comes from the mother, so that means I’ll be pulling 100g out from the mother each time I bake: so 250g mother is a good baseline, a little over twice what you take out at any given time. It doesn’t hurt to have too much mother, but too little is risky.

Your starter should smell good. Yeasty bready, maybe a little tangy if it’s been sitting for a minute. If it collects a liquid on top, that’s hooch—you can just pour it off. Mold means it’s time to start over.

Baker’s percentages

Bread recipes are typically given in baker’s percentages, where all of the ingredients are relative to the amount of flour used.

I typically bake 500g loaves, i.e., loaves with 500g of flour in them (the total weight is closer to 900g!). Such a loaf will last two adults for several days, if not a week. If a 500g loaf has 75% hydration, it will have .75 * 500 = 375g = 375ml water in it; if I’m using 20% starter, I’ll have .2 * 500 = 100g starter; if I put in 2% salt, it will have .02 * 500 = 10g salt. You could of course bake a bigger loaf. A 600g loaf with 70% hydration will have .7 * 600 = 420ml water.

My equipment

To bake bread, I use:

- A ~1L tupperware container for holding the mother.

- A 6qt food safe plastic bucket with lid.

- A scale accurate to a few grams.

- A silicone-headed spatula or stirrer for mixing the starter and the mother.

- A plastic or silicone soft dough scraper for getting the dough out of the bucket.

- A bench scraper for shaping the dough.

- A plastic cutting board or melamine counter for shaping the dough.

- Two 500g bannetons for proofing.

- Two plastic grocery bags for covering the bannetons. They should easily fit over the banneton without touching the contents.

- Two Lodge 3.2qt cast iron combo cookers for baking.

- An oven… surprise! It should be able to comfortably get up to 450ºF.

- A safety razor for slashing the dough.

- A metal spatula for getting the bread out of the pan.

- A cooling rack.

You need a scale. Some people can bake good bread without weight measures, but not me. If you’re only going to buy a single piece of equipment other than a scale, get the combo cookers—their steam trapping effects will significantly improve your bread.

You don’t need a special bucket. You don’t need bannetons. You don’t need a combo cooker. You don’t need a razor or any of those scrapers. These are the tools I’ve learned to use because they help me treat the dough gently (to keep those precious gas bubbles!) or result in substantially better loaves in some other way.

You’ll also need the bread ingredients, of course—wheat flour, salt, water, and sourdough. If you’re using bannetons, you’ll want to mix up some banneton flour: a 50/50 mixture of AP flour and rice flour.

Before using bannetons for the first time, I lightly dampen them with a spray bottle (or my hand) and then rub a bit of AP flour into them. Get all the nooks and crannies and all the way up the sides. Shake out the excess and let them dry. You’ll still get a bit of sticking your first few times using them, but then it should even out. O’Malley just goes ahead and uses them without any treatment, though I think he gets more sticking at first.

My recipe

My core recipe uses 75% hydration, 20% starter, and 2% salt. I typically bake two loaves at a time, though. Here’s my two-loaf recipe broken down in each possible way:

| Ingredient | Percentage | Actual amount in a loaf | Total amount I use to make two loaves |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flour | 100% | 500g | 1000g |

| Water | 75% | 375g | 750g |

| Starter | 20% | 100g | 200g |

| Salt | 2% | 10g | 20g |

But I live in Claremont, CA—the edge of the high desert. On the humid East Coast, I use significantly less hydration—65%, or 650g for two loaves.

My procedure

My baking has several stages. I’ve written approximate active and passive times for each, and I’ll break down the recipe along these steps.

| Step | Active time | Passive time | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Making the starter | 5min | 6-12hr |

| 2 | Mixing up the dough | 10min | |

| 3 | Autolyse rest | 20-60min | |

| 4 | Kneading | 5min | 30min |

| 5 | Turning (2-3 times) | (each) 2min | (each) 30min |

| 6 | Bulk fermentation | 2-12hr (or overnight) | |

| 7 | Shaping | 10min | 30min |

| 8 | Proofing | 1-3hr (or overnight) | |

| 9 | Baking | 5min | 30-60min |

| 10 | Cooling | 2min | 1hr |

| 11 | Cleaning up | 5min | 12hr |

I’ll give a high level overview of my approach, and then I’ll give detailed steps.

I make up a starter well before I’ll be baking. If I want to bake in the morning or early afternoon, I’ll make the starter up in the morning the day before. If I’m baking in the late afternoon or evening, I’ll make the starter in the evening the day before.

Making up the starter also means feeding the mother: you just took something out of the mother, now you’ve got to put it back in. Both mother and starter will need to be left alone out of the fridge to develop, after which you can mix up the dough. After the initial mixing, the dough rests. A serious first knead is followed by several turnings and rests. Once the dough has been turned a number of times, I let it sit until it’s more or less doubled in volume. Then I shape the dough, let it proof in bannetons, and bake. Finally, I always let my bread cool for half an hour—but ideally an hour or more—so that the steam stays inside. If I cut into a loaf in less than half an hour, I plan on finishing it within a day, so it doesn’t get stale.

Okay: how does it work? Throughout, I give concrete amounts. You can just halve all of the weights to get a procedure for a single loaf.

Making the starter

- Take the mother out of the fridge.

- Put 100g of the mother into your bucket. This is your starter.

- Add 50ml of water to the mother and 50ml of water to the starter in the bucket. Mix each thoroughly with the silicone spatula.

- Add 50g of flour (AP or bread) to the mother. Add 50g of flour (whatever you like) to the starter. Mix each thoroughly.

- Put the lids back on for both the mother and the starter.

- Let the mother and the starter sit out until they show obvious signs of fermentation. In hot weather, this could be as little as 3 hours—maybe less if it’s really hot! In cold weather, it’s probably overnight.

- Return the mother to the fridge.

Your starter is now ready to be made into dough, but it could be returned to the fridge and still used profitably within 24 hours.

Mixing up the dough

- If your starter was in the fridge, remove the bucket.

- Add the 750ml water. On the East Coast, I’ve found 650ml to be the right amount. The water temperature will determine some of the fermentation speed: the warmer the water, the faster the fermentation. Never add water over 100℉.

- Add the 20g salt.

- Stir the starter, water, and salt with the silicone spatula. It doesn’t have to be completely homogeneous, but try to mix it well.

- Add the 1000g flour. In your first few batches, I recommend sticking to white AP or bread flour. When using a mix of whole and white flours, I tend to add the whole first, since it’s thirstier and tends to clump more. You can prevent clumping by adding a bit of flour, stirring, and then adding a bit more.

- Stir with the spatula until the dough is homogeneous and there’s no visible powdery flour.

- Put the lid on the bucket.

Autolyse rest

The bread gets a moment to relax; the flour soaks up moisture.

- Leaving the dough at room temperature, wait 20 minutes or up to an hour.

Kneading

The bread gets a thorough kneading and rest before going through a series of turns and rests.

- Remove the lid from the bucket.

- Wash your hands.

- Leaving the dough in the bucket, mix the hell out of it. Reach in there and just really go for it. I’ll do a series of pinching maneuvers on one axis (say, left to right) and more pinches on the other axis (say, top to bottom). After a few pinches in either direction, I flip the bread over and keep going. I’ll knead for a few minutes—not longer than five minutes, but enough time to feel the dough start to come together beyond what the early mixing did.

- Put the lid back on the bucket.

- You’re gonna want to wash those hands again. If you have a septic tank, try to avoid getting the flour mixture down the drain—it can gum things up. O’Malley wipes his hands with a paper towel.

- Wait 30min, then start the turns.

Turn, turn, turn

Here’s how to turn the dough:

- Remove the lid from the bucket.

- Wash your hands.

- The bread is sitting in a round bucket, but imagine that it’s actually a square. You’ll fold each side onto itself. That is:

- Reach in and grab the bread from one side. Pull it up and fold the bread on top of itself.

- Reach in and grab the bread from the next side (say, clockwise). Pull it up and fold it on top of the already folded bread.

- Reach in and fold the next side.

- Reach in and fold the last side.

- Reach in and under and turn the entire dough upside-down, so that your folds are on the bottom. If you work quickly while folding, there won’t be much sticking and it’ll be easy to flip the bread. Don’t worry if you feel like you’re mangling it—it gets easier. If trying to pick up the dough mangles it, give it another four turns and try again.

- Put the lid back on.

- Let the dough rest 30 minutes.

Repeat. Two turnings is the minimum; I’ll typically go for four. With each turning, the dough should take on more form, holding together better, standing more upright and sticking to the sides less.

Bulk fermentation

You’ll want at least two turnings before bulk fermentation starts. Bulk fermentation is a geologic process, with the usual trade off: time vs. pressure. Fewer turnings means more time in the first rise, while more turnings means less time in the first rise. Just like in geology, heat changes the equation, speeding things up.

I often let the dough bulk ferment in the refrigerator. This is called a ritard, because it slows down the whole process. That might seem like a bad thing, but it’s actually great. More time means more flavor! Plus, sometimes you just don’t have time to finish baking right now. Don’t worry: you can stop the dough at just about any time in the bulk fermentation and put it in the fridge. (If the dough is already moving fast, you won’t be able to buy that much time. But you can definitely buy some!)

Conversely, you can speed things up by, say, warming your oven to 200℉ for 10min, turning it off, and then letting the dough ferment in there. You’ll get less flavor, but it’ll happen on your schedule.

- Let it sit until the dough doubles. In my 6qt bucket the 1000g bulk will sit just below the 2qt graduation before rising, and is ready to bake somewhere between the 3qt and the 4qt.

Shaping

There are lots of ways to shape the dough. First, the general idea.

- Flour whatever bannetons you’ll be using with the 50/50 AP/rice flour mixture. You don’t need much, but if your dough sticks when unmolding, use more flour next time.

- Use the soft scraper to pour the dough out onto the cutting board. I don’t normally flour the board first.

- Using the hard bench scraper, split the dough into two roughly equal sections. If you totally misestimated, no worries: just cut a bit off the bigger one and glom it onto the smaller one.

- Lightly wet the bench scraper. It should be damp but not actively dripping; I run it under the faucet and then briskly shake it off.

- Shape the first loaf into a round. That is:

- Use the scraper to fold the dough onto itself (say, front to back).

- Use the scraper to refold the dough onto itself again, in the opposite direction (say, left to right).

- Holding the bench scraper vertically, bring its flat side towards the dough and drag it around clockwise anywhere from a quarter to a three-quarter turn. (Go counterclockwise, if you’re left handed.) Keep pressure towards the center of the dough as you go around. This should have the effect of shaping the dough into a round. You can also do this step with your hands, but using the scraper means less handling, which leaves more gas in the bread.

- Repeat until the dough is starting to ball up nicely. Not more than five.

- Repeat steps 4 and 5 for the second loaf.

- Let the dough “bench rest” for up to 30min.

- If you’re using a banneton, loaf pan, or other bread former, put it in now. (Instructions below.)

- Check the banneton to make sure the dough will unmold: with wet or floured hands, pull up on the loaf to make sure it isn’t sticking to the ribs of the banneton. If it is, pull back the dough and sprinkle in a bit of banneton flour where it was touching. You can preemptively sprinkle a bit on the dough just off the edge where it touches the banneton, too—as the dough rises during proofing, that will be the part that pushes out and could stick to the banneton.

- Cover the bannetons loosely—make sure the covering won’t touch the dough, even as it rises. Plastic grocery bags are good for this, since they’ll stand up on their own.

Here’s how to shape for round bannetons and for oval, bâtard bannetons.

Round bannetons

- Do 10 or so turns around the dough, trying to stretch the outside of the dough a little. Re-wet the bench scraper as needed.

- Slide the bench scraper under the dough ball. Using the scraper and your off hand, invert the dough into the banneton (gently!).

Oval bannetons—shaping for bastards

- Sprinkle a bit of AP (or other wheat, or rye) flour on top of the round.

- Slide the bench scraper under the dough ball. Using the scraper and your off hand, invert the dough onto your board. As you transfer it, try to deform it into a slight oval. I form it with the long axis from 12 to 6 on an imaginary clock while standing at 6 o’clock, but you can do it with the long axis from 9 to 3; whatever works for you.

- Stitch up the dough. With your right hand, use your two forefingers and thumb to grab a bit of dough from the left towards the top of the oval and stretch it over, pressing it onto the right side. Then use your left hand and grab a bit from a bit below where you pressed in the last ‘stitch’; press it onto the left side. Repeat until you’ve ‘sewn’ up the loaf.

- With a hand at the top and the bench scraper at the bottom, pick up the dough and gently transfer it into the banneton.

Loaf pans—shaping for sandwich lovers

I quite like using Pullman loaf pans to make bread with a lovely, square profile—or, without the lid, to make a beautifully domed loaf.

- Stretch the dough into a rectangle a little longer than your pan and about half again as wide.

- In order to have a uniform crumb, de-gas the bread: aggressively pat the rectangle all over.

- Roll the long edge of the dough about 1/3 of the way towards you.

- Fold the short edges over.

- Pull up the other long edge, pinching the seam shut.

- Place seam side down in a Pullman loaf pan; cover with lid, if you like.

Proofing

Proofing is a second rise. It can take as little as 30min (a hot day when your dough more than doubled and the starter’s been fed recently) or several hours (a cold day when your dough didn’t quite double and you heavily worked your dough during shaping).

- Let the shaped loaves sit in the bannetons until they’ve adequately risen. This is the hardest part to explain. A good test is that a wet finger depressed half an inch into the dough gets a slow, even rebound. Fast rebound needs more time, no rebound means overproved. But… the loaf in the video below has only the slightest rebound, but it was a tiny bit underproved.

- Put combo cookers into an oven set to 425℉. I find it takes about 30min to get the pans up to temp. It’s hard to know when to start the oven: you want the oven to be ready the moment the loaves are fully proofed. I’ll start the oven when the dough’s rebound is still strong but starting to slow down.

You can prove effectively in the fridge, too, though the rebound effect will be even harder to read. Bread that’s been risen and proofed entirely in the fridge will have subtle bubbling all over the crust and a nice tang (cool temperatures favor the bacteria over the yeast). You can put fridge-proofed loaves right into the oven or let them sit on the counter for a bit.

Baking

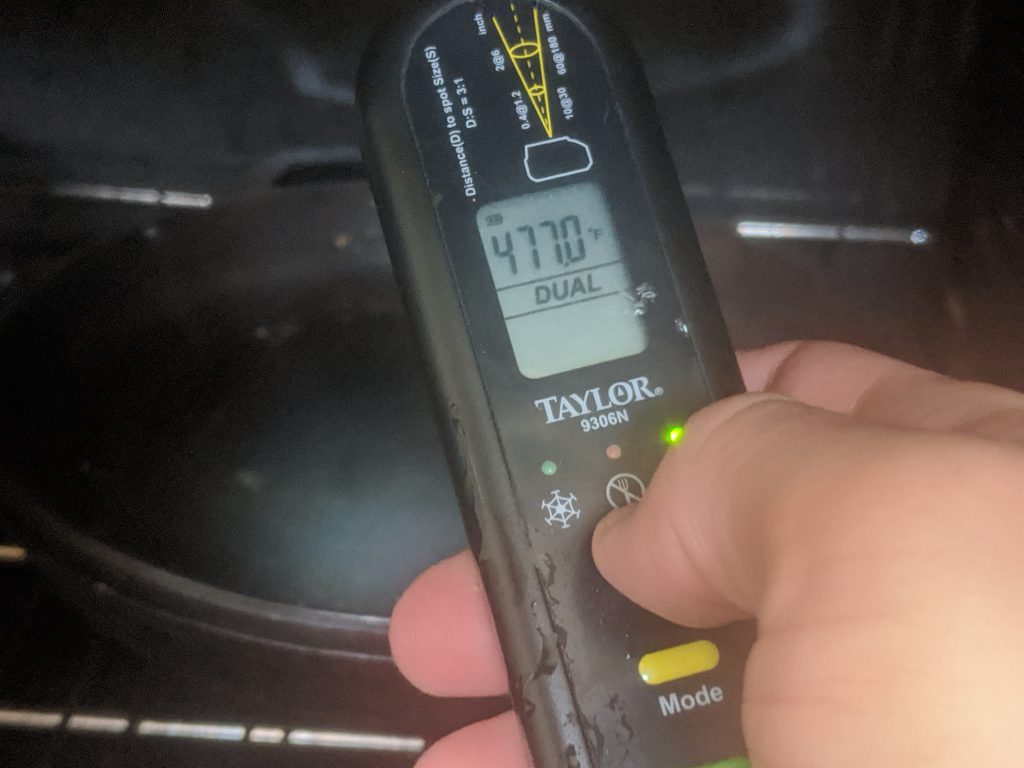

If your proof has been very brief, make sure that your combo cookers are hot (400℉ or greater). An infrared thermometer is good for this.

- Remove the plastic bag covering one of the loaves.

- Check to see that the dough will unmold. With damp or floured fingers, see if you can pull the edges back from the banneton. If it’s sticky, pull it back and touch it up with a bit of banneton flour (and use more banneton flour next time).

- Remove a combo cooker base and lid and place them on top of the oven. Don’t forget to use oven mitts… those pans are hot!

- Unmold the loaf into the base (the shallow part). You can do this with a ‘tip and flip’, or you can put the banneton down on the counter, invert the combo cooker base on top, and then flip the lot. Your banneton will be fine with the heat of the pan—it’s only a second or two. If the dough sticks in the banneton, give it a few good taps. If that doesn’t unmold the bread, start to lift the banneton, rotating it around a bit as you go to loosen the lot. You may have to reach in with your fingers—be careful not to burn yourself.

- Slash the dough. I’ve had poor luck with a lame, so I use a safety razor bare-handed. (A sharp knife works well; bread knives tend to do a good job.) Be careful! If the dough is perfectly proofed, you can do a number of a nice slashes: an X, three horizontal, a leaf, etc. If the dough is over- or underproofed, make smaller and fewer slashes.

- Put the lid on the combo cooker base and put it in the oven. You may need to use two hands.

- Do the same for the other loaf.

- Set a timer for 15min.

- When the timer goes off, open the oven door and remove the combo cooker lids.

- Bake until the loaves are done, another 20-45min. Go by color and smell. Breads with whole wheat are particularly good with a touch of singe on the ears. After a few minutes of cooling, I brush off and then stack the combo cooker lids.

Cooling

- Turn off the oven.

- Pull a combo cooker base from the oven.

- Remove the bread from the pan using a metal spatula. Using the spatula upside-down will let you get your hands on it. (You may need oven mitts.)

- Put the loaf on a cooling rack.

- Set the base on top of the lids.

- Repeat for the other loaf.

Do not cut into warm bread. It’s not done cooking yet! If you cut into it now, you’ll lose too much moisture and your bread will have a dry, spongy texture (instead of the light, fluffy one you want!) and go stale quickly. If you’re going to completely finish the loaf the day you bake, though, knock yourself out.

Cleaning up

I never really clean my bannetons, but I’ll pick off crusted-on dough. Everything else should be cleaned thoroughly.

- Wash the silicone and metal spatulas, board, bench scraper, and bucket lid immediately after using them.

- Once they’re fully cooled, scrape off any burned-on bread from the combo cookers and wipe them down with a damp cloth or paper towel to remove any flour. Make sure they dry completely—I either leave them out for a few hours or put them back in the warm oven with the door open for a few minutes.

- Leave the bucket and the soft dough scraper out to dry overnight. When the leftover dough is fully dried, it should flake off easily. Put the flakes in the trash rather than clogging your drain, then wash the bucket and the scraper.

Playing around

Start out just using AP or bread flour. I’ve come to quite like 40% Grist & Toll flours (3:1 Sonora and charcoal wheat) and 60% AP, but play around. I’ve used just about all kinds of wheat flour in bread, but plain AP yields a nice, tender, white crumb with a thin, crispy crust. Plain bread flour will develop a bit more gluten for a firmer crumb and thicker crust. European breads baked with bannetons tend to be baked with lower protein flour, while American bread flour is really ideal for free-form, sturdy country loaves. I like to incorporate stone ground whole flour, like that made by Grist & Toll or other small mills, and I’ve also included “00” a/k/a doppio zero and durum flour. You can go 100% whole or 100% white or anything in between. You can include pastry flour, too, for that tender crumb.

You’ll have to play with hydration levels. Whole wheat is thirsty, and Grist & Toll flours are very thirsty. I’ll go above 80% hydration when using a lot of whole wheat. I go as low as 60% when baking on super-humid Martha’s Vineyard.

There’s a certain feeling to getting the hydration just right. Sticky, cookie-like dough means you’ve not got quite enough water in it. Sloppy dough that doesn’t gain structure with each turning is too wet. You’ll have to play around with the flours you use, how vigorously you knead and turn, the ambient temperature, etc. You’ll know when you’ve got it right, since the dough feels just great.

You’ll know when you’ve proved correctly because of the excellent oven spring with beautiful ears and a nice clear dome. That is, the loaf will be substantially larger than the dough you put in the oven, the slashes will have grown craggy and sharp, and the top of the loaf will have risen not just up, but out.

Don’t feel bound by my particular strategies for kneading or turning. Use whatever method you like, though I’d caution you against overhandling the dough. If you want a nice, big loaf with a beautiful rounded top and an open crumb, you need to be very gentle with it. Don’t knead on a board unless you want a tight crumb for sandwich bread.

Play with shaping! For a while I was shaping by hand, where I’d form a boule, gather up the craggy ends on the bottom, and then put those directly into the banneton without inverting. That is, I’d form a boule and the ugly bottom of the round would become the top of the loaf. It was erratic and craggy… fun! I’ve also been happy with using lidded Pullman pans to bake sandwich bread. Checkout The Perfect Loaf’s recipe for Pain de Mie for info on loaf pans and shaping.

It’s tricky to control how sour the dough is. The longer the mother sits between feedings, the more sour it’ll be. The colder it ferments, the more sour it’ll be. But I’ve had poor luck trying to control it, and I suspect that my starter is just mellow and yeasty. Your starter will adapt to whatever environment and treatment you give it.

If you’re just feeding, try using the starter to make waffles or pancakes. I’ve made hamburger buns, pizza, and focaccia with great success, too. You can take just about any recipe with yeast, drop the commerical yeast and add in 20% starter (in baking percentages!). That is, if your conventional-yeast recipe calls for 500g flour, you’ll want 100g of starter instead of the conventional yeast. That starter will have 50g of flour (25g from the mother, 25g added) and 50ml of water (25ml from the mother, 25ml added). You’ll want to deduct those quantities from your recipe to account for their presence in the starter. To make your converted recipe, just treat the starter like you would the yeast. Be patient, but it should be great!

Don’t feel bad about wasting flour during feedings. Worst case, the leftover starter is great for compost.

Troubleshooting

If the crumb is too tight, the dough is most likely overworked and underrisen/underproofed.

If the dough doesn’t seem to rise, try waiting longer. Sluggish mother means sluggish starter. Regular baking and feeding help.

If there’s a seam of undercooked dough near the bottom of the loaf, your dough was too cold and probably underrisen and/or underproofed.

If the loaf busts open new ‘ears’ or, worse, tears during the oven spring, you didn’t slash deep enough and you may have underproofed. If your slashes went flat, your dough was under- or over-risen, under- or overproofed, or you slashed too deep.

Also: it’s gonna be fine. Even your worst breads will usually be edible. (If you accidentally leave out the salt, mix salt and chilli flakes into olive oil, dip your bread into it, and pretend you’re in Tuscany.)